BooleaBayes Part 3- Using data to build a network for Small Cell Lung Cancer

We’ve talked about why we care about transcription factor networks. We’ve talked about what the structure and rules of a network might look like. In this post, we’ll talk a little more specifically about how we can use high-dimensional data from sequencing experiments to determine the structure and rules of a network.

In the last post, in the party puzzle, I gave you rules for each person– how they decide whether or not they want to go to the party. But how do we figure out what these rules should be, if we don’t know them ahead of time?

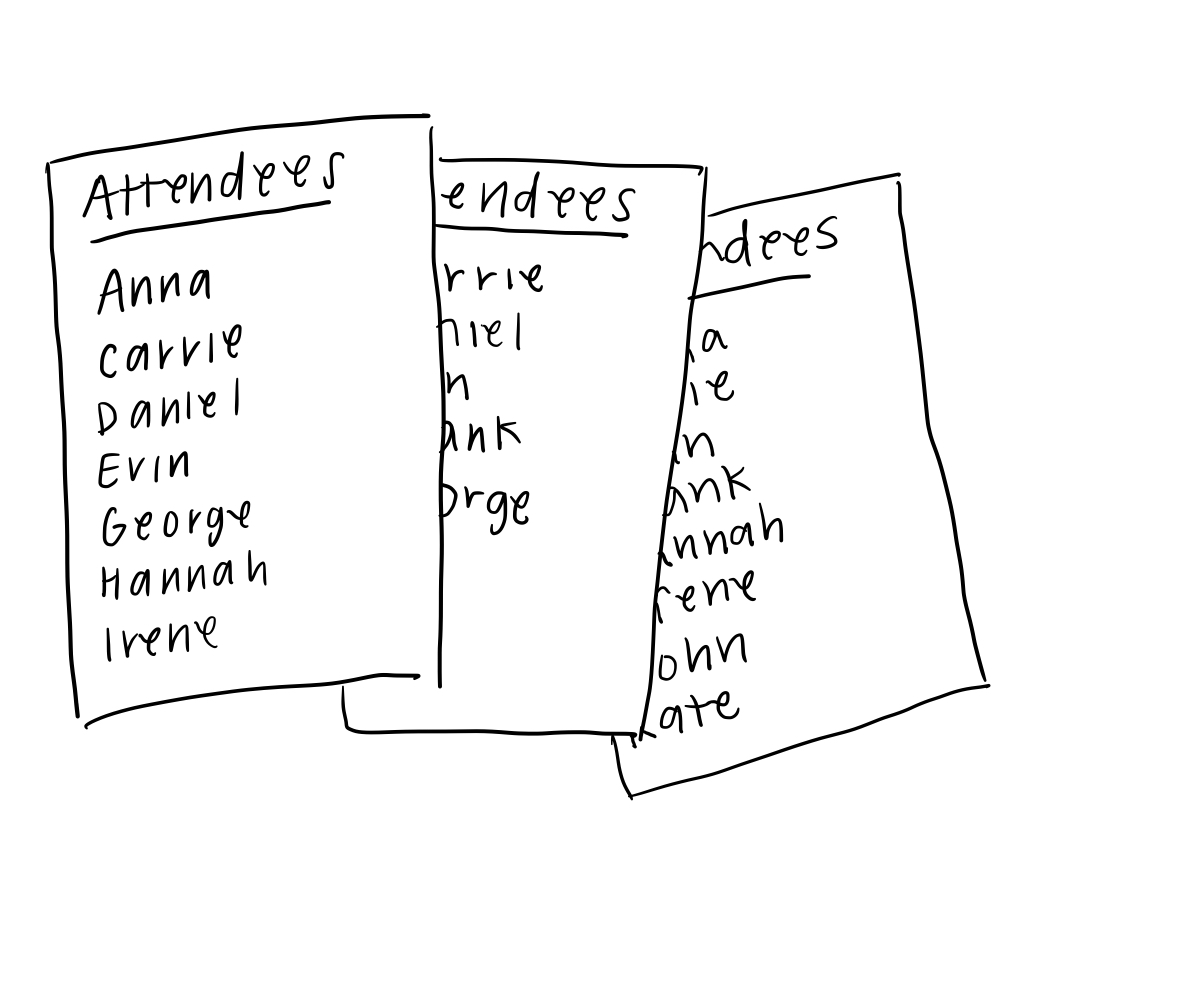

In terms of the party puzzle, we might have a scenario like this:

- There have been quite a few parties in the past, and attendees were recorded each time (“samples”).

- Each person always used the same “rule” to decide whether they will go or not– the rule is considered time invariant.

- We want to figure out these rules for each person, even though we only know who went to each party.

This is a really hard problem, and could be considered a problem of reverse engineering. In fact, it’s hard enough that it would be difficult for me to even come up with a list of “past party attendees” (samples) that would allow you to find a unique set of rules for everyone.

What would make this problem easier?

Maybe we could use our knowledge of who’s friends with who (and who’s enemies with who) to make an educated guess about what influences each person’s decisions. For example, if we know that Carrie is good friends with Daniel, we might assume that Carrie will base her decision on whether or not Daniel decides to go (this is, in fact, her rule). This is called “prior knowledge,” or often in biology, “expert knowledge.” Expert knowledge is often how we come up with the connections in a transcription factor network.

Gene regulatory networks (or transcription factor networks) can be made for an abundance of biological systems, including cancer. I focus on Small Cell Lung Cancer, which is an extremely deadly form of lung cancer. While SCLC patients make up only 15% of lung cancer patients, the five-year survival rate is around 6% (compared to ~25% for other types of lung cancer).

Just like we talked about in the first post, Small Cell Lung Cancer cells can easily change their cell identity. Sort of like a deranged differentiation, SCLC cells can change cell types according to what functions they need to optimize. Early on, it seems like cells start in a proliferative cell type that can grow the tumor quickly. In later stages, some cells can change to a cell type that is good at migrating to other places in the body, thereby seeding metastases in places like the lymph nodes and brain. Interestingly, we think this is how cells are able to avoid death from chemotherapy; some of the cells die from chemo (and the tumor will shrink), but we think some change their cell identity and evade the treatment, allowing the tumor to eventually regrow.

If we can understand and control how cells change their identity, we may be able to develop more effective treatments for this deadly cancer.

We already talked about what we need to learn to figure this out: how is the transcription factor network controlling these changes in cell identity?

To answer this question, we developed a tool called BooleaBayes– an algorithm that can take in data and reverse engineers the rules of the network controlling that data. Just like in the party scenario, we first would like to figure out the structure of the network, which we do using expert knowledge. There’s a really cool type of experiment that can figure out what proteins (transcription factors) are binding to what pieces of DNA (genes). It’s called ChIP-seq, and essentially the method uses a cool trick to “tie together” any proteins that are bound to DNA (normally in a live cell these proteins will bind and fall off the DNA pretty quickly). The scientist then “shakes up” the DNA to break it into little pieces, and pulls out the pieces of DNA with the specific transcription factor of interest bound to them. Once these pieces of DNA are sequenced, the scientist can figure out which genes are controlled by that transcription factor. This is akin to determining the edges in the network: which proteins (transcription factors) affect other genes?

Lucky for us, many of these experiments’ results have been compiled into databases, so we looked at the databases to come up with a network connecting transcription factors we know are important in SCLC.

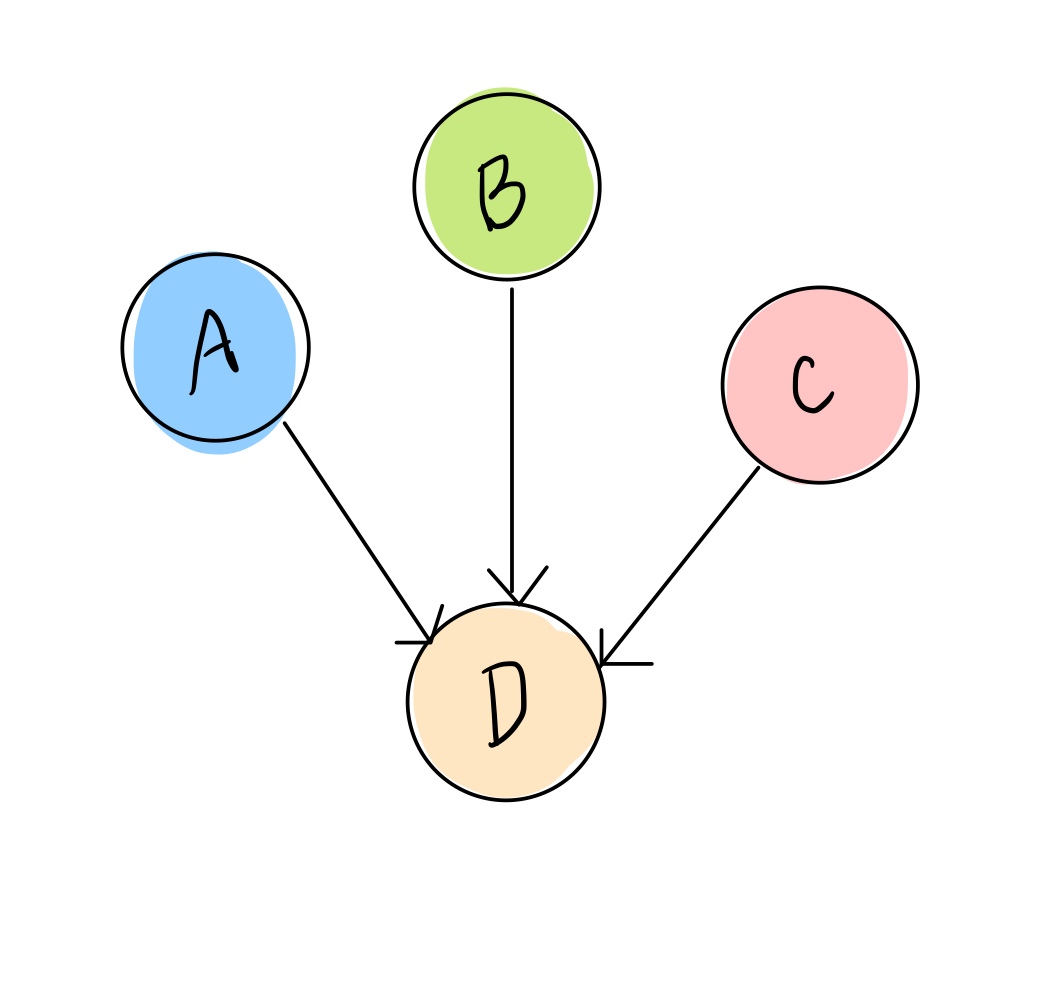

So we have a good idea of which proteins are affecting other genes. But how? For example, we might know that proteins A, B, and C affect gene D, but the rule could be many different things:

- D expression = A and B and C

- D = A or B or C

- D = A and B and not C …

To determine which one is the right rule, we need some data. This is the second (main) piece of our BooleaBayes algorithm: we use sequencing data to determine what rules define the interactions between transcription factors. Don’t forget the big picture here:

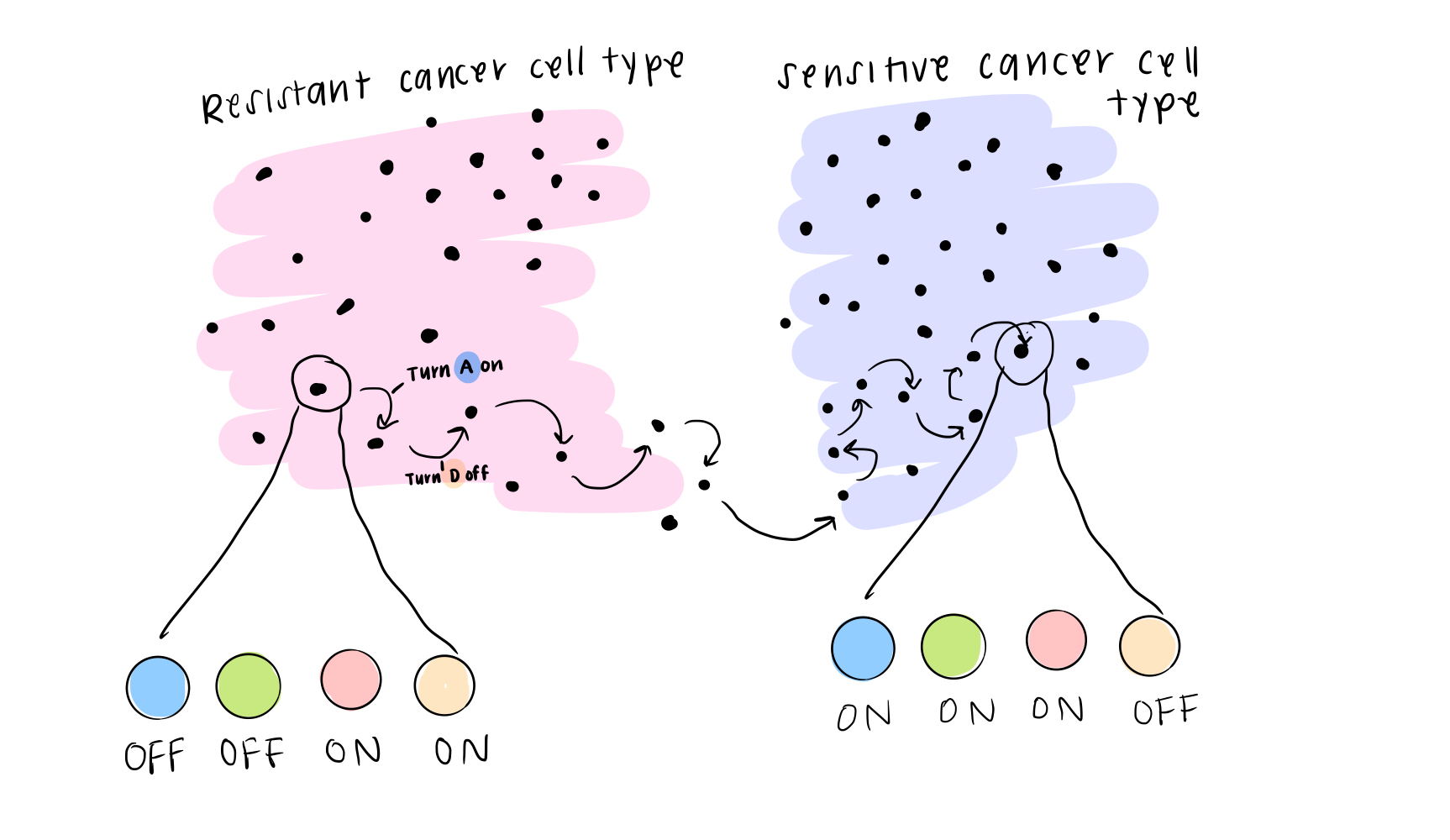

If we know how transcription factors interact with each other (by figuring out the rules), we can understand– and control– changes in cell identity, and hopefully change recalcitrant cancers into easy-to-treat ones.

Similar to our party example above, if we have many “samples,” in this case with different levels of transcription factors in each one, we can determine which transcription factors are co-expressed (positive relationship) and which are inversely correlated (negative relationship). Let’s look at another example, more specific to our current problem.

We’ll consider a simple transcription factor network with only 4 genes, A, B, C, and D:

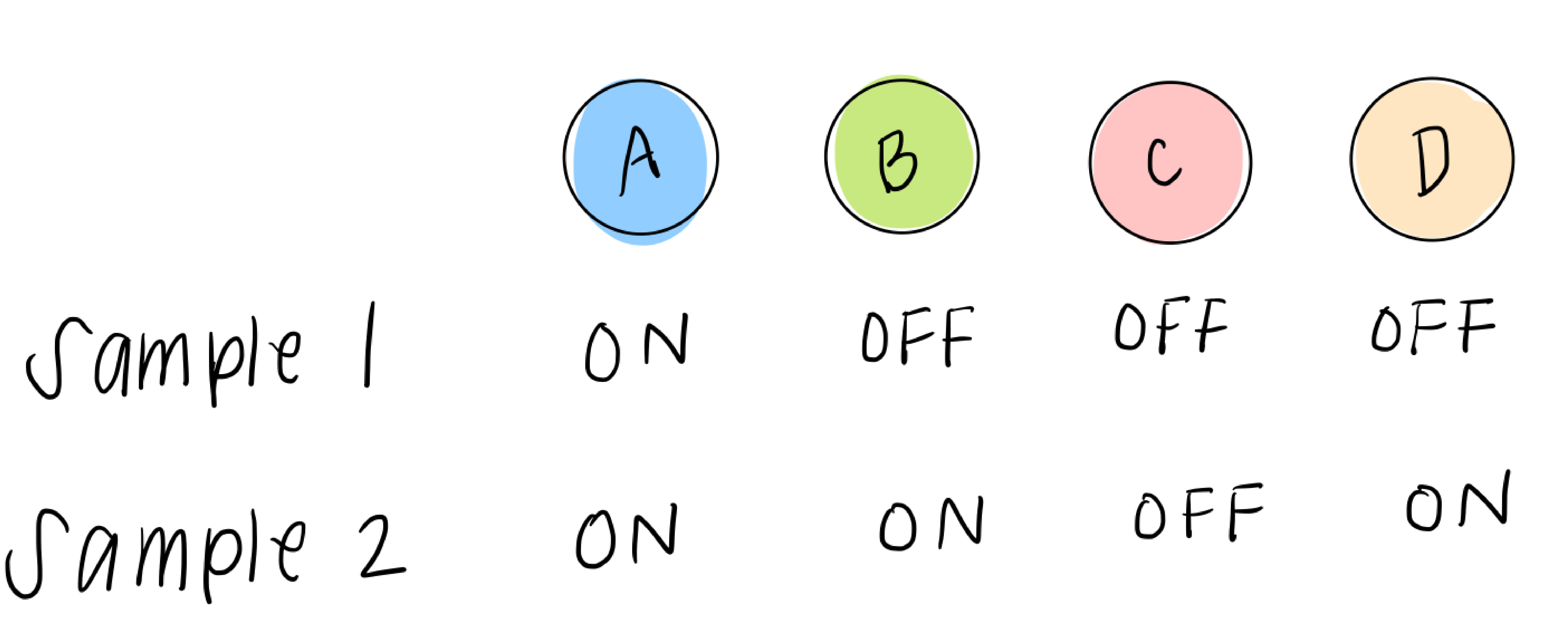

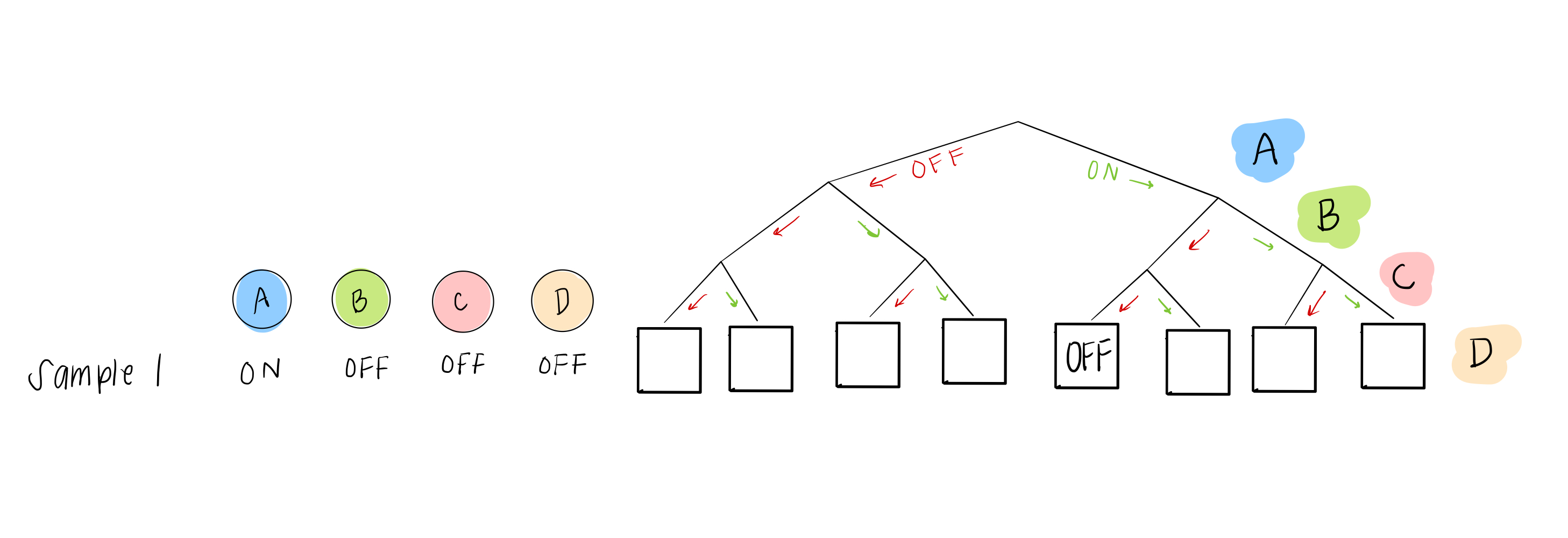

We also have data that tells us, for RNA sequenced from different samples (which could be different people, tumors, mice, etc), which transcription factors are highly expressed in that sample and which are low. We’ll simplify this, as we did above, to two options: ON or OFF, yes or no, 1 or 0. So each sample data point will look something like this:

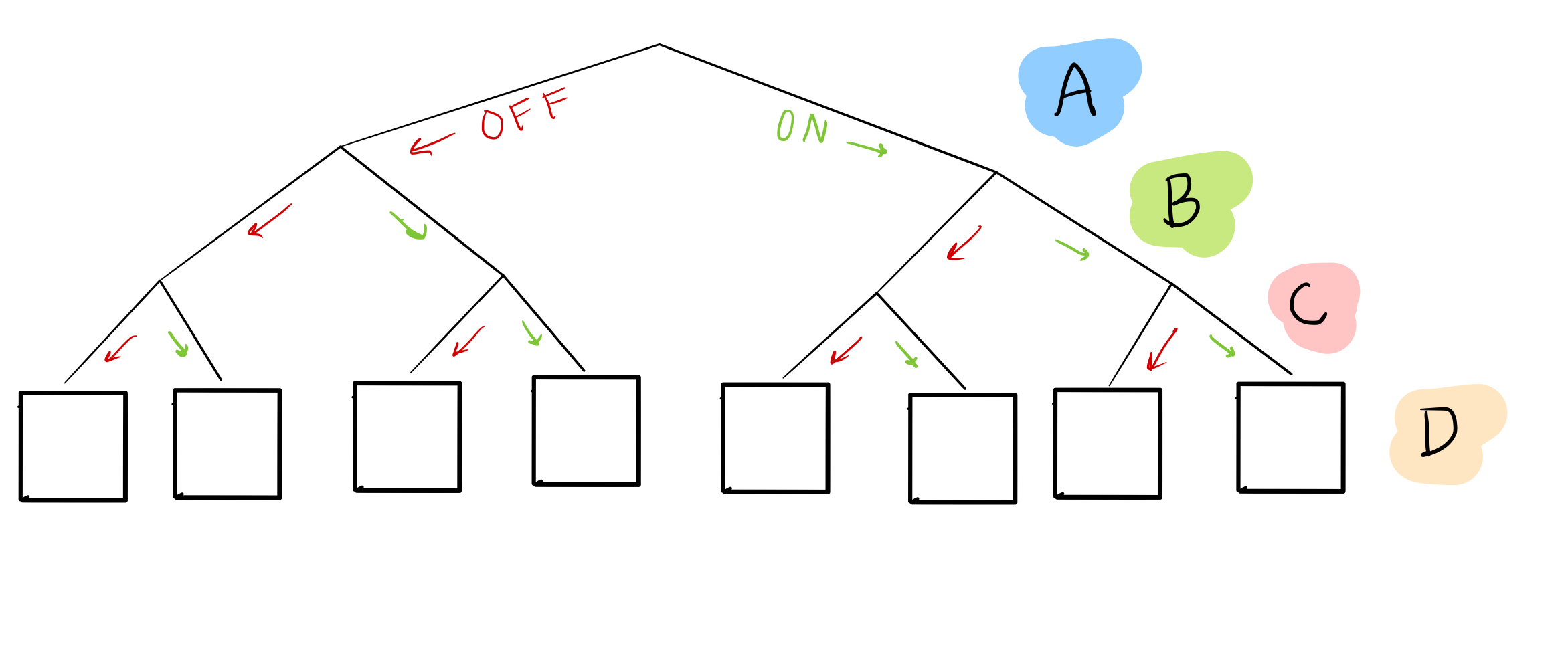

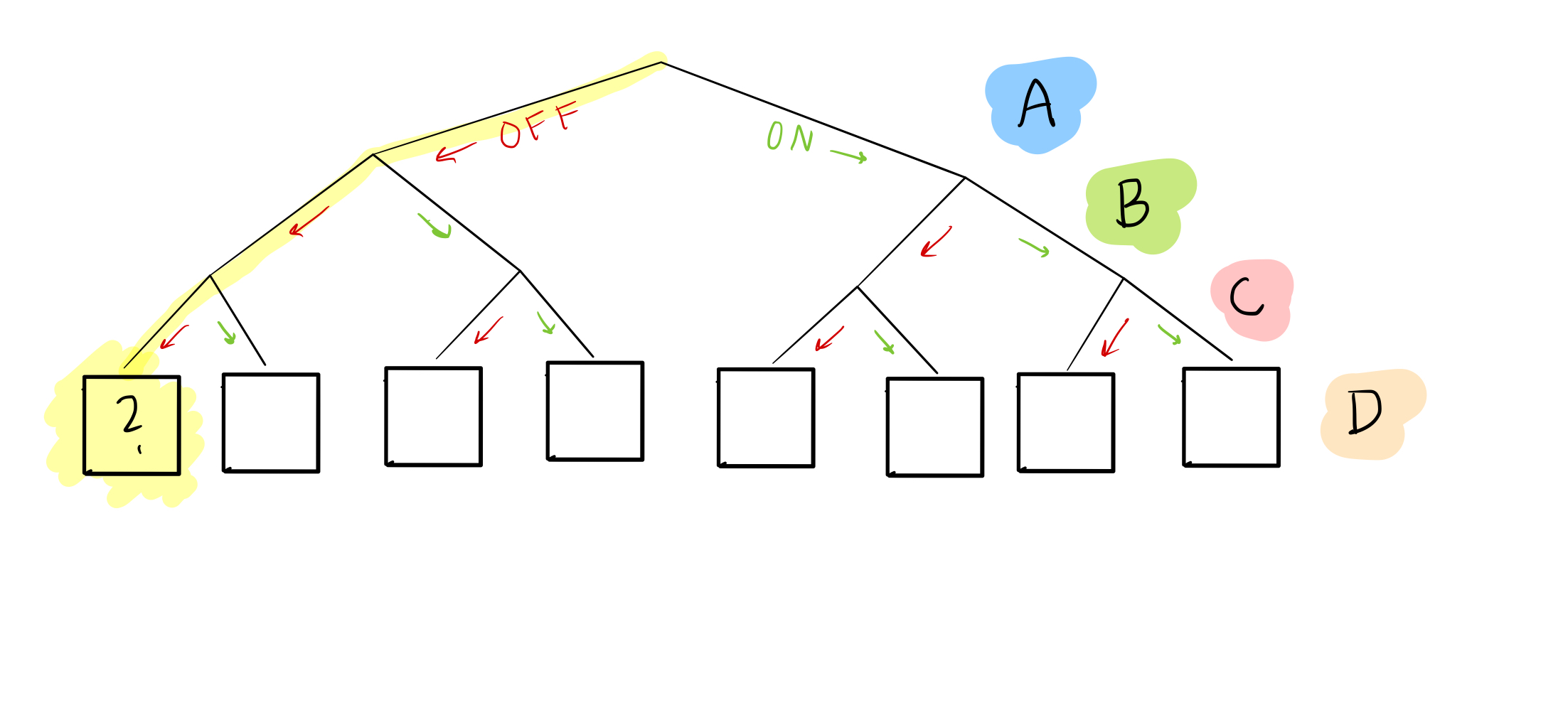

Remember how, in the last blog post, we considered every possible combination of the “parent nodes,” or the ones affecting the thing we care about, by making a table? We can represent this in another, more compact, way:

In this “tree,” we’ve enumerated every possible combination of nodes A, B, and C as leaves at the bottom. For example, if we want to know what happens when A, B, and C are all off, we can look at the first leaf:

Or when A and B are off, but C is on:

Right now, we don’t know what goes in the boxes for node D: that’s the goal!

What we do have, though, is sample data, which gives us some possible combinations of A, B, C, and D. For example, sample 1 can help us figure out what happens in the 5th leaf from the left:

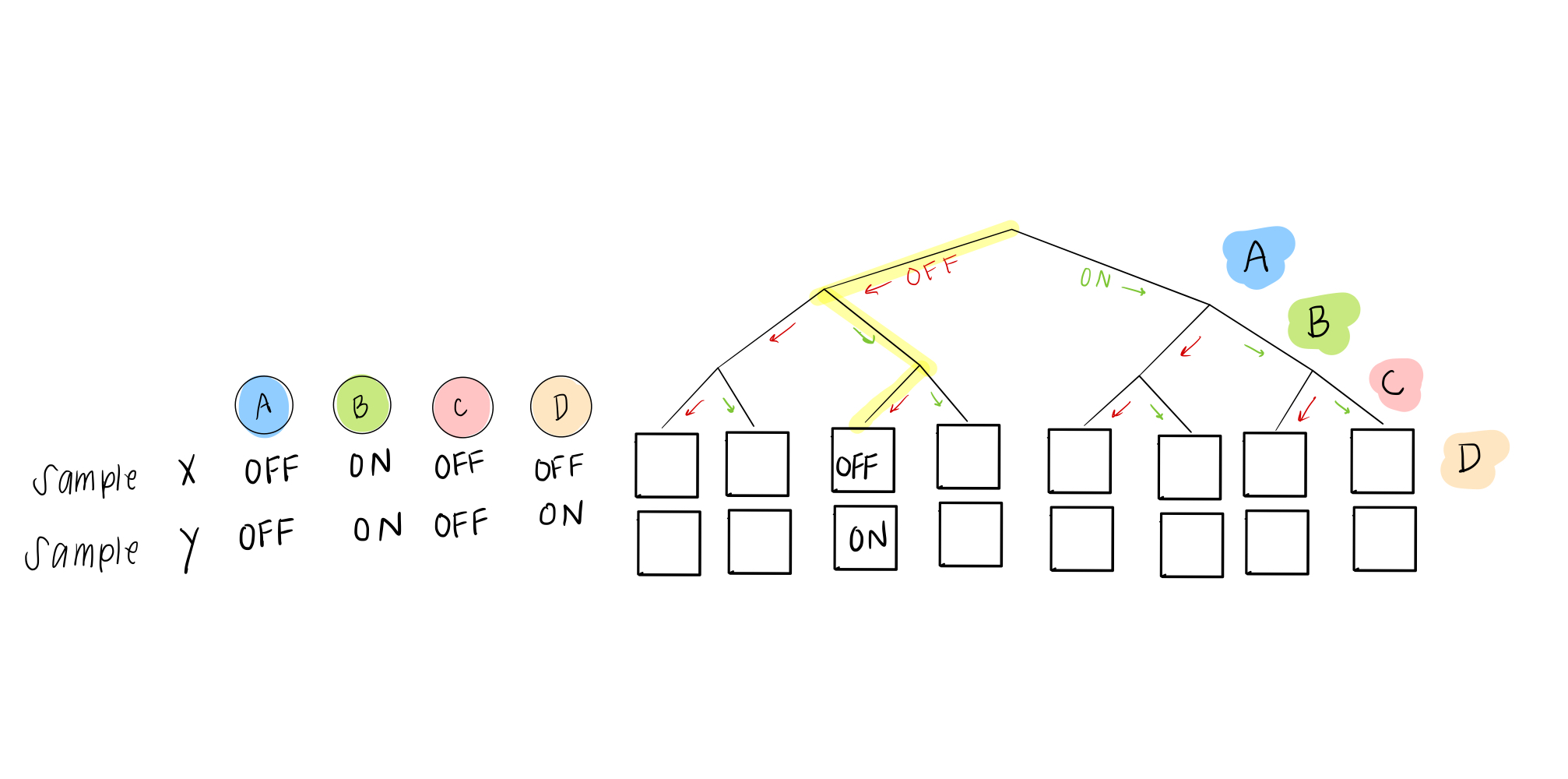

and sample 2 can help us with the 6th leaf:

If we have enough samples, we can fill in all the nodes!

Even though this “rule” isn’t in English, like our party rules were, it gives us the same information: for every possible combination of ON and OFF (going vs. not going) of our parent nodes (friends), we know what will happen to some affected gene (person of interest). So if we have a rule like this for each node in the network, we’ve solved our problem! We know which transcription factors will turn on (“who goes to the party”) no matter what configuration of ON and OFF we start with.

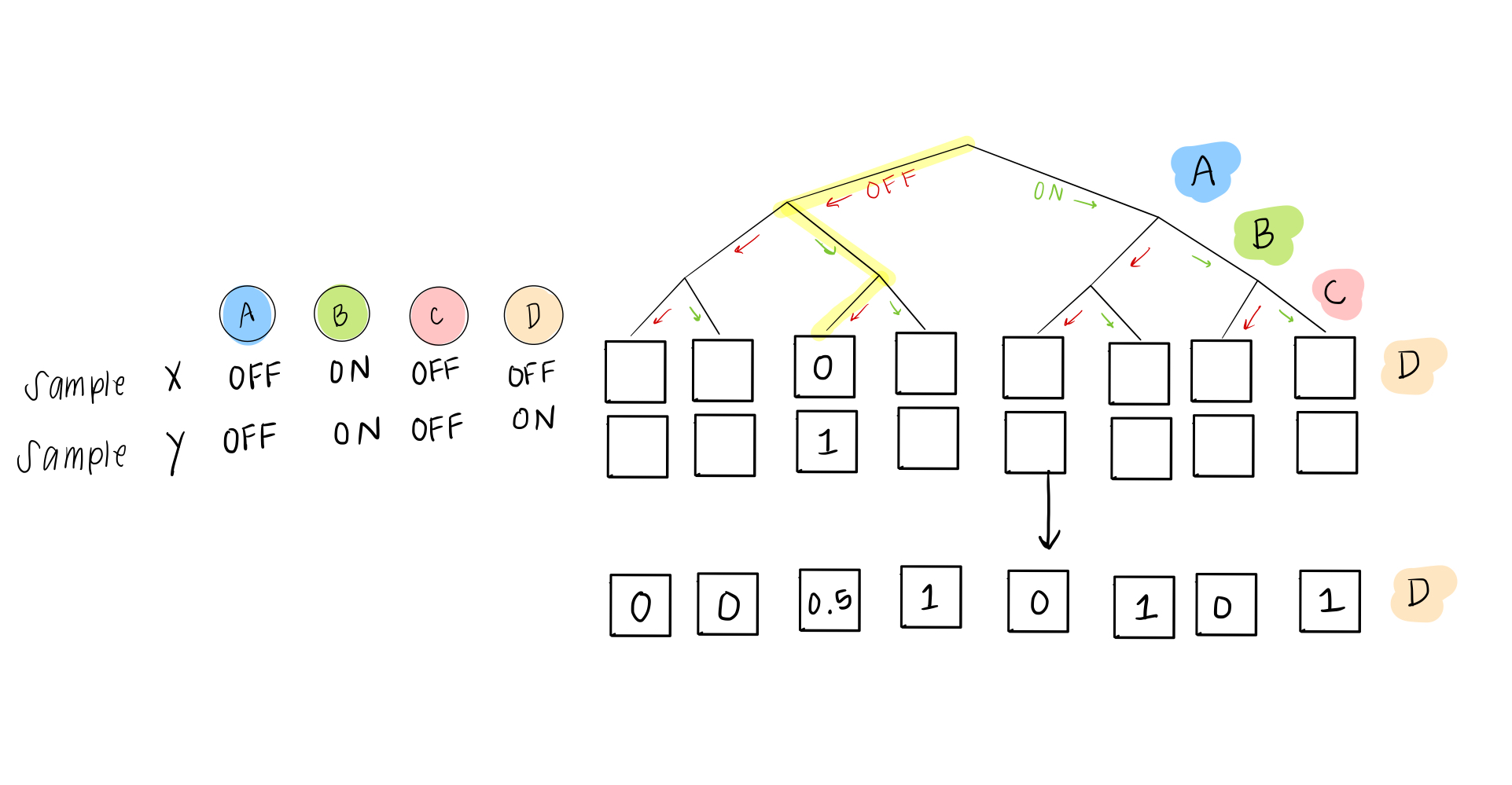

Not so fast! you say. What happens if two samples don’t agree? This might happen when a cell is in the process of changing its identity (phenotypically transitioning), multiple similar cell types are stable and thus found in the sample data, or it might just be due to noise in the system.

Our solution is pretty easy. Even though we eventually want to describe everything as either ON or OFF, in these rules, we can give a probability of being ON (or OFF). So instead of a 0 or 1, in the case of two “disagreeing” samples, we would have this scenario:

This is basically the same as a situation where Carrie will go 50% of the time if Daniel goes– if Daniel is going, she flips a coin to decide; if he isn’t going, she still won’t go either.

At the end of the previous post, we used tables and state transition graphs to “move through different states” and figure out who was going to the party. Another way to visualize this is like below:

We started at some (random) starting state, and then slowly updated our knowledge of who was going and who was not until our knowledge didn’t change anymore. In the picture above, we “move” from one state to another, slowly updating them, until we reach a state where we don’t move anymore.

We do a similar thing with these rules for our transcription factor network, now moving through “gene expression space,” where transcription factor expression for each gene can be ON (1) or OFF (0).

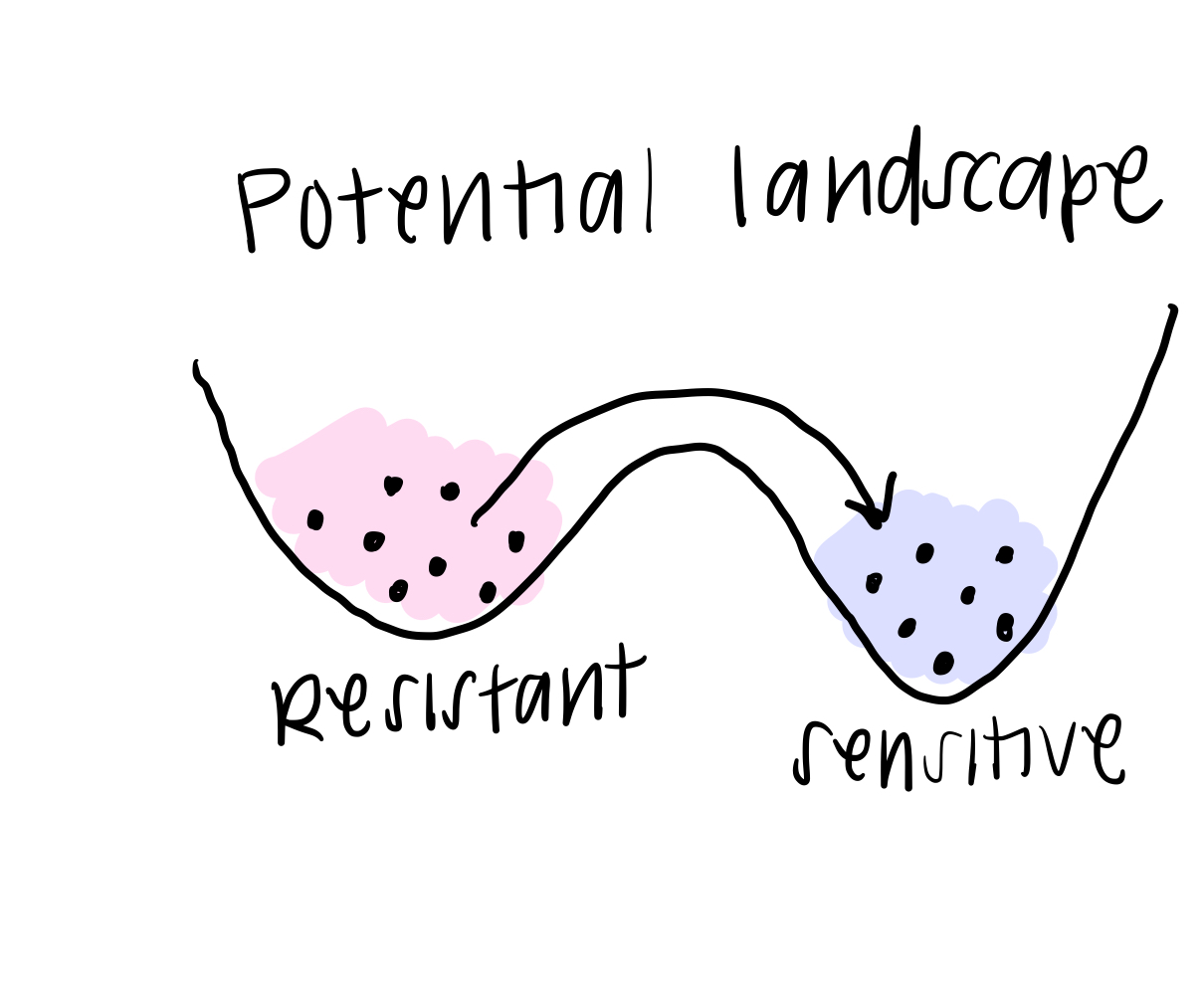

The final piece of the BooleaBayes algorithm is to simulate this movement through the gene expression space. You can think of it this way: if a cell happened to find itself in a state that was “not allowed,” according to the rules, it will quickly move away from that state towards a more stable one, where it is stable. This is like a ball at the top of the hill (in the first post) rolling down to a valley and coming to rest. When we simulate a system, we use the rules we just found, along with some starting state (that probably is meaningful biologically), and we watch where the cell moves until it becomes stable.

In real life, this is how we think about cells changing their identity: they might get a small “push,” or signal, from their environment to change away from their starting state, and the rules of interaction determine exactly how they change identity.

In a paper by David Wooten, PhD, and me, we find a network for Small Cell Lung Cancer cells, and use it to figure out what will happen if we start in different states, and where the stable states are. This gives us some ideas for how we might control the cancer cell’s identity, by predicting different perturbations we can make (for example, getting rid of a transcription factor entirely or turning it all the way up) that would change a cell’s ability to function. If we change cancer cell identity just right, we might be able to make them susceptible to treatments we already have in the clinic.