BooleaBayes Part 1- The Why

Have you ever thought about how different cells in your body came to be? You may have heard that you have a particular genome that is shared by virtually all of your cells. So why does, for example, a heart cell act so differently from a lung cell? How does a cell located in your heart learn to “turn on” heart cell functions, and “turn off” lung cell functions? And if you took that heart cell and moved it to the lung, would it be able to change its function and start acting like a lung cell?

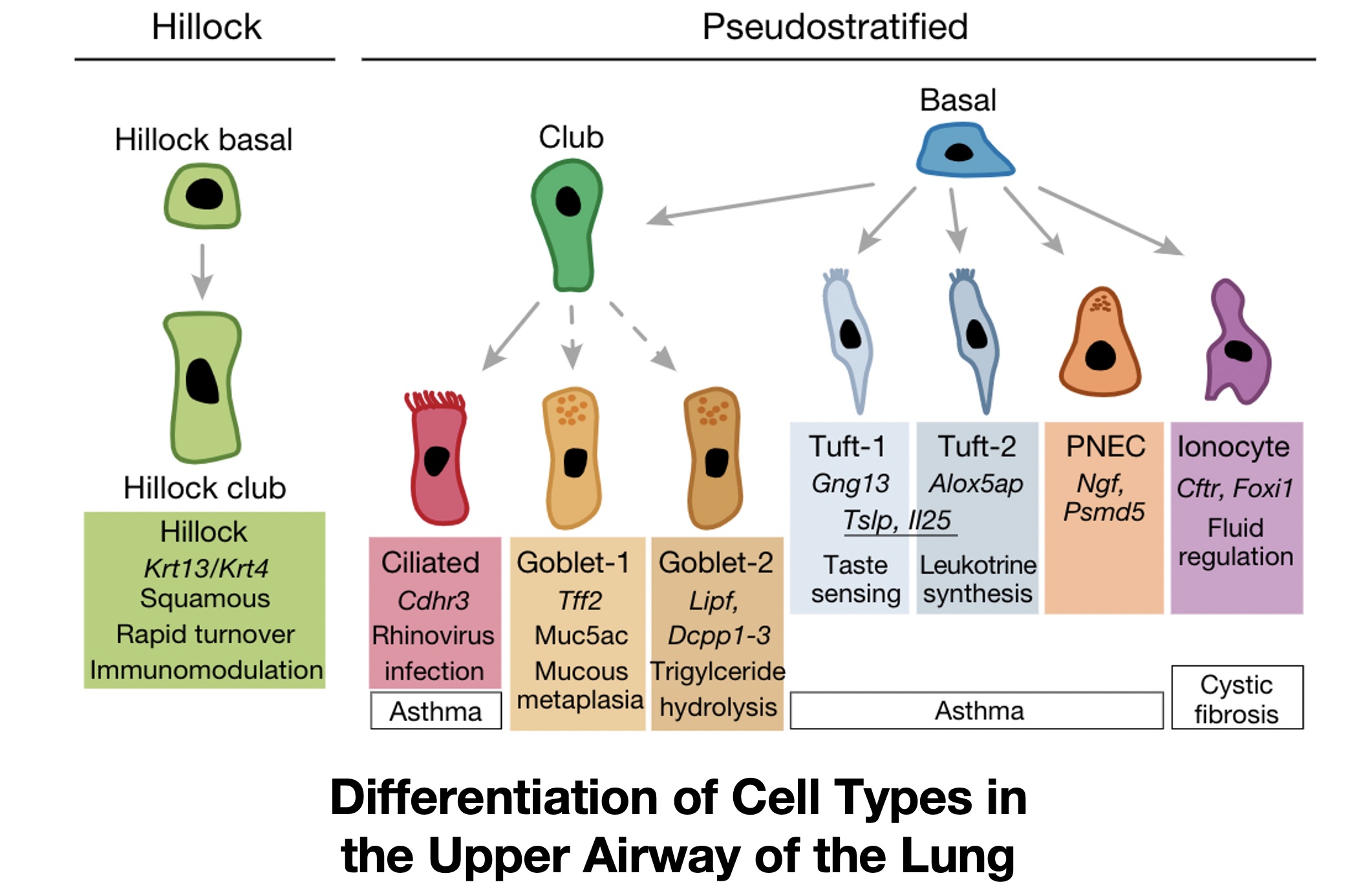

These are all questions of cell identity. Cell identity can be defined in many different ways, but generally we think of a cell’s identity as the array of functioning proteins that cause a cell to have specific behaviors, whether that is in terms of interaction with other cells, functions in the body, or in response to external signals and perturbations. For example, the figure below shows a variety of cell types that exist within the lung, all of which have distinct functions, such as moving air and particles through the trachea (ciliated cells), cells that produce surfactant to protect the lung epithelium (club cells), or cells that assist in lung development and recovery after injury (Pulmonary Neurendocrine Cells, or PNECs).

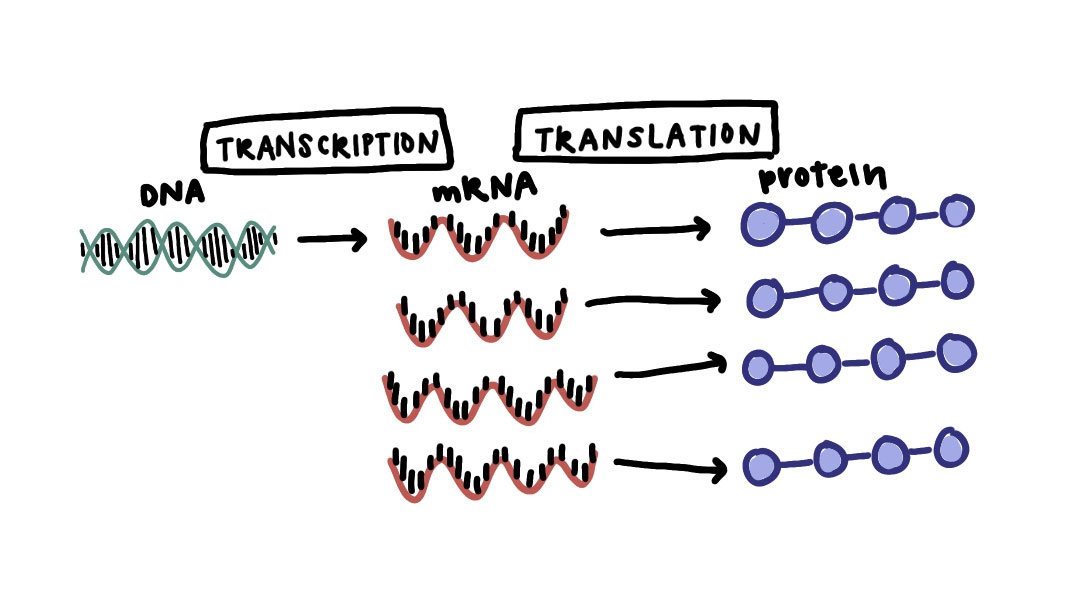

All of these cells likely have the same genome, or specific patterns of DNA, if they come from the same (healthy) person. But they have different phenotypes and proteomes (amounts of an array of proteins in each cell), which can be driven by non-genetic processes at the transcriptomic, or RNA expression, level. So a cell’s identity– distinguished by its behaviors– is governed by the expression of genes required for certain functions.

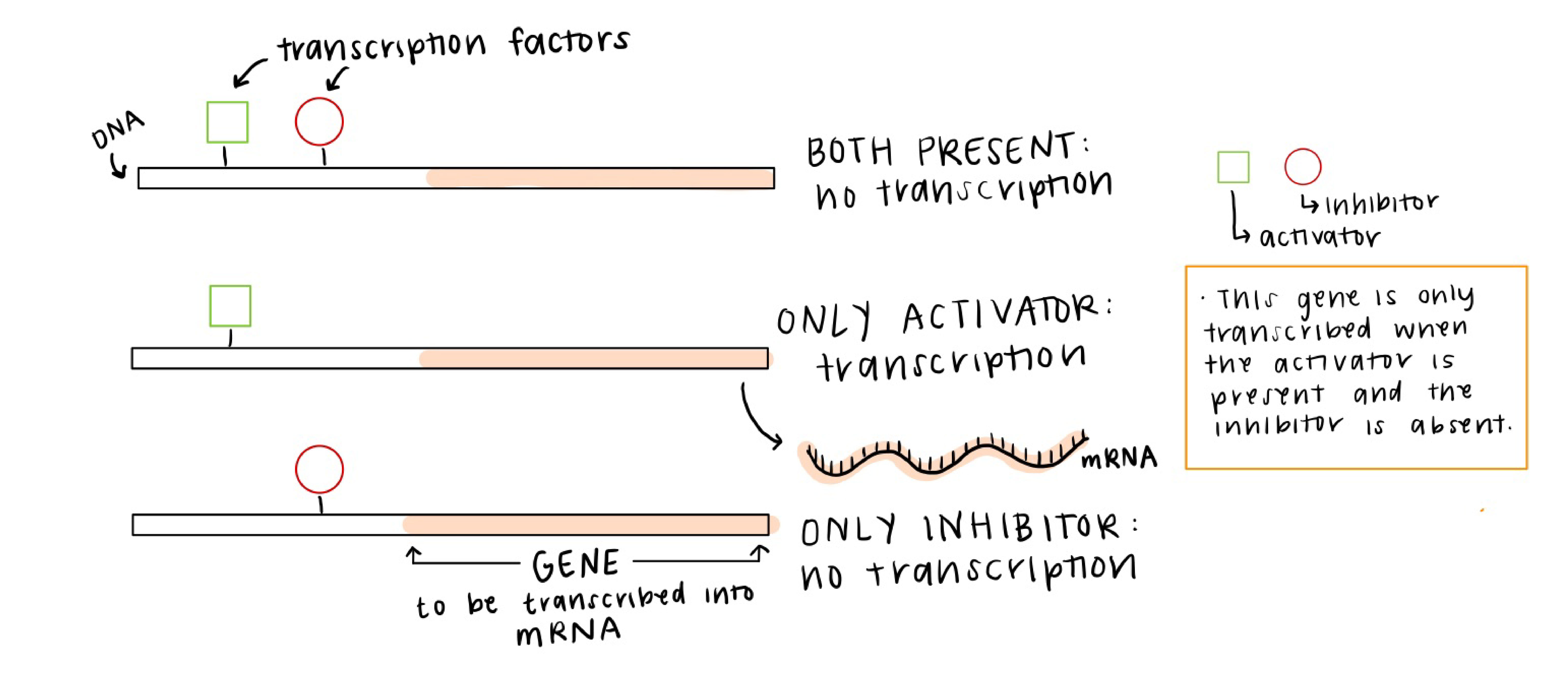

Often the control of gene expression, or transcriptional regulation, is ascribed to networks of transcription factors that affect the level of gene expression (amount of that gene’s RNA) in each cell. For example, the image below is showing three different TFs (two activators and one repressor), and when the TFs bind to their targeted regions of DNA, they affect how much of the target gene is transcribed and therefore how much of that protein is made.

These TFs do not work independently, but instead can be placed in a network that we call a gene regulatory network (GRN). Sets of interacting transcription factors (TFs) can “drive” cells towards a specific “identity” through concerted activities. GRNs can exist in multiple states and their dynamics can explain the coexistence of multiple stable cell types even within an isogenic (same genome) population. These dynamics also give cells the plasticity they need to undergo epigenetic changes necessary for response to perturbations and external signals. For example, in response to an external signal, the dynamics of the network shown here may cause the green gene expression to increase and the blue to decrease until the cell’s expression profile reaches a stable point. These dynamics of gene expression are how a cell might change its phenotype– for example, from a lung basal cell to a club cell.

Because this single network under different conditions can produce varying phenotypes, we say that the network is capable of explaining the multi-stability of cell phenotypes that share a single genome.

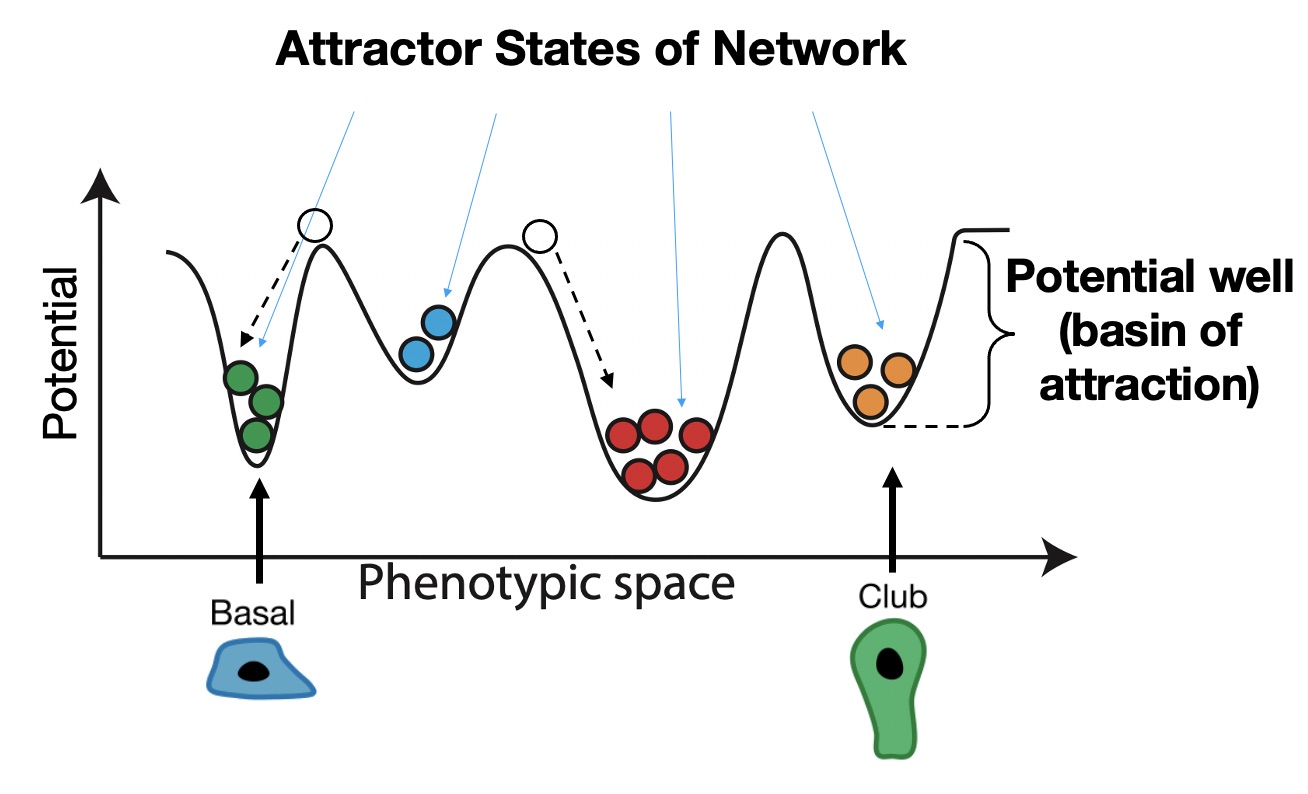

A very helpful (albeit limited) visualization tool for thinking about multiple stable cell types is a phenotypic landscape. If you have not heard of a phenotypic landscape before, it is an idea that was first proposed by a guy named Waddington to describe how cells differentiate from one cell type to another without necessarily changing their genome. You may be very unlikely to see a heart cell turn into a lung cell, but these types of changes in cell identity happen all the time in differentiation: a stem cell turns into more specialized cell types with specific functions. Waddington proposed that differentiation was like a ball rolling down a hill and falling into basins at the bottom of the hill that represent different steady states, or cell types. Here, we’re showing just one dimension of the landscape across the x axis, but you can think of each point on the x axis as a different cell type, and the y axis is the stability of that cell type. Similar to a ball rolling down a hill, if we place a cell someone on this landscape that is not in a basin, it will roll down into a nearby basin until it comes to a stop.

Where these cells stop are called attractor states in the network, and these correspond to stable cell phenotypes we would see empirically, such as the basal and club cells we saw before. Importantly, attractor states are self-stabilizing, which means that if you perturb a cell by moving it a small distance from the attractor, it will roll back to its original starting place. We therefore think of the stability of each attractor as the depth and relative size of the basin of attraction surrounding it. Often this stability comes from feedback loops in the underlying network of interactions.

In cancer, cells are defective in how they replicate DNA and partition it to daughter cells during cell division, which is a state we’ll refer to as genomic instability. This may be caused by defects in DNA repair, cell cycle checkpoints, improper apoptotic signaling that would normally cause cells with defects in the genome to die.

Genetic instability is accompanied by non-genetic instability, or “plasticity,” meaning cancer cells are often able to traverse the landscape more easily. This is epitomized by the idea of a cancer stem cell, which has stem-like properties such as its proximity to immature attractor states. In normal development, there is a gradient to the landscape from stem cells to more stable differentiated cell types; thus, stem cells sit near the top of the “hill” and differentiated cells near the bottom. Cancer cells are pushed toward these abnormal cancer attractors in normally unused regions of the landscape that often look more and more like dedifferentiated cell types, with properties such as high proliferation and phenotypic plasticity. We think that this plasticity– the ability to reach a more stem-like cell state that can shape-shift into other cell types when needed– is what allows cancer cells to cope with, and eventually overcome, treatment. For Small Cell Lung Cancer, for example, within 5 years around 95% of patients succumb to cancer after they have already been treated and the cancer came back.

So now we come to the problems we are trying to solve:

How do cancer cells change their identities, and what can we do to stop them from changing into resistant cell types?

Our answer: control the underlying regulatory network to control cell identity and keep the cells from becoming resistant in the first place. This is what the BooleaBayes computational tool does: it figures out the specifics of the GRN (how the transcription factors affect the expression of genes and which ones), and uses it to predict what would happen to each cell type if we were to make a sudden change in the network. If we find a change we can make that keeps the cells from turning into a resistant cell type, we can test that change using a genetic modification in a mouse, and eventually by targeting that gene in humans.

See the next post to learn how we determine what the gene regulatory network looks like.